We who make carvings do not duplicate drawings or photographs; we carve what we see in our minds. . . . Being able to leave something that people remember you by long after you’ve passed on is something to look forward to. I am happy that I will be able to leave something of myself after I die. . .”

(Jimmy Arnamissak in Inuit Art Quarterly, 1997)

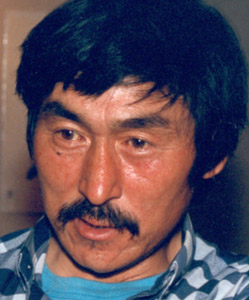

Born in 1946, in an area between Akulivik and Inukjuak called Ilaittuq. Arnamissak later moved to Puvirnituq, eventually settling in Inukjuak.

Arnamissak’s father, Silassie, was accidentally killed during a hunting trip, leaving his mother, Louisa, to support the family. To supplement his mother’s pension, he began carving in 1959, when he was about 14 years old. “Because I had no father I had to think of some way to earn money. By watching and learning from other Inuit who were carving [including his mother and Simeonie, his brother], I started to make carvings, and have continued ever since” (Arnamissak in Inuit Art Quarterly 1997:26). The first carving Arnamissak did was of a woman with outstretched arms holding a kudlik (oil lamp). “I remember us [he and his mother] laughing hard together when I made my carving, because the woman was carrying an oil lamp in her arms. I put some real seal fat in the lamp and it was funny because it was so real” (Arnamissak in Eisemon 1989:46).

Sculpture.

Arnamissak’s detailed carvings, with their smooth contours and compact arrangements, convey a strong sense of activity and narrative.

Along with hunting, Arnamissak’s mother, who died in 1975, was the subject of many of his sculptures. Louisa’s facial features can be seen in his carvings of female figures, and many of his works were based on the theme of the active mother and wife busily engaged in domestic activities. He was also known for scenes of northern life, which often include groupings of people, kayaks, dog teams, igloos, and sleds arranged on flat, oblong bases. As a hunter, Arnamissak also liked to depict wildlife, even though, as he said, creating an accurate portrayal was difficult:

I look at animals very closely when I am hunting. But when it comes to carving, even though I want to try and make it as close to what the animal looks like, it’s hard. When you put it in stone you cannot make it as you saw it, because when you carve it, the stone will break. It’s not easy to make it look exactly the same as the animal — to make it look real (Arnamissak in Eisemon 1989:37).

Arnamissak’s later work included snowmobiles, partly because he regularly travelled hundreds of miles to find and quarry stone, which was hard work. As he said,

we have never used machinery like bulldozers to extract soapstone; the only tools we use are shovels, so it’s a bit of a hardship. . . I’ve been told by a Qallunaaq (white person) that the Inuit land is thought of as a land of soapstone. It seems that is how southerners think of the North, when, in fact, it is very difficult to get, because we have so much snow in the winter. The only time to try and get soapstone is when the snow has melted” (Arnamissak in Inuit Art Quarterly 1997:27–28).

Arnamissak’s vignettes of daily life have a degree of detail and sense of motion and action that seem to defy the solid nature of the stone from which they are carved.

In 1984, Arnamissak travelled to Tokyo to participate in an exhibition at the Canadian Trade Centre, an event sponsored by La Fédération des Coopératives du Nouveau-Québec. In 1986, his work was included in an exhibition of Inuit and African soapstone carving that was shown in the Kisii district of western Kenya. He later participated in an exchange with Kisii carvers, organized by McGill University’s Faculty of Education.

Arnamissak’s later work reflects a thematic change: “I liked older times then, and I still do. They used to live in igloos and ride in kayaks and use dog teams. Back then, I carved only the older Inuit culture. . . Now I carve new things like ski-doos and canoes. I get the ideas for these carvings just by following the Inuit way of life . . . just by following the changes” (Arnamissak in Eisemon 1989:45).

Apart from a brief period in the 1970s when he worked as the manager of the cooperative in Inukjuak, Arnamissak devoted his entire life to carving.

1987 “Inuit and Kenyan Artists Share Experiences,” in Inuit Art Quarterly (IAQ), vol. 2, no. 4 (Spring): 10.

1989 Stories in Stone. Montreal: La Fédération des Coopératives du Nouveau-Québec.

1998 “Jimmy Arnamissak: ‘I am happy to leave something of myself,’” Inuit Art Quarterly (IAQ), vol. 13, no. 3 (Fall): 45.

1997 “Jimmy Arnamissak: ‘Leaving something that people remember you by,’” Inuit Art Quarterly (IAQ), vol. 12, no. 1 (Spring): 26–29.