The future of carving, in my opinion, and based on my thoughts on the next generation, is that they will show who we are, our ‘Inuitness.’ They exist for this reason — they show the ability of Inuit. They also show what it was like in the past — our legends — what it was like in the old days and who our forefathers were. My children will know me through the carvings I have made, and those who buy them will know who I am.”

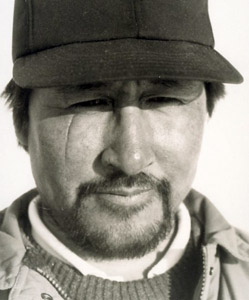

(Jobie Uqaituk in Art Nunavik, 2009)

Our way of living has changed, but when our youth see carvings depicting the old ways, they know that we aren’t just making up stories. How we carve should not disappear. I’m happy that I’m helping preserve our culture through my carving.”

(Uqaituk in Inuit Art Quarterly, 1998)

Born in 1946 in Kutaaq, north of present-day Inukjuak.

“In 1956, when I was 10 years old, I remember holding onto a heavy stone, trying to figure out what I was going to make with it. I made what I was comfortable with — a bird. I’ve never forgotten it or the stone. It was a good stone — green and red. That year, I sold my first carving to the Hudson’s Bay Company. I was given a pair of mitts for it, although I was hoping to get candy. My mother had told me that I couldn’t even do the finishing sanding on the carving because I was too young. But I have been carving ever since, and, when I’m not carving, I’m out hunting. My life hasn’t changed in all these years” (Uqaituk in Inuit Art Quarterly 1998:40). “It was very difficult for me when I started carving. . . . To me, it was something unknown and I had no idea how to do it. I forced myself to make something out of stone that would be understood” (Uqaituk in FCNQ 2009).

Although Uqaituk had been carving for many years, he did not dedicate himself to artmaking until the early 1990s. He says: “I began taking even more care in my sculpting, increasing my enthusiasm for it. It was a bit like starting over again” (ibid.).

Although Uqaituk carves, he also produced a number of prints, including a self portrait, at the Inukjuak print shop during the 1970s.

Uqaituk explains that obtaining stone is a painstaking process:

Quarrying stone is hard work. . . . It slows you down a lot. You have to use a hammer, an axe, and then a shovel to get rock out of the ground. After you get the stone, you have to think about what you’re going to do with it, what the movement is going to be, what the meaning is. That is hard. It is difficult when you are trying to make something with meaning and life. . . . You can take pictures with a camera and try to carve from that, but it’s hard to put it into stone” (Uqaituk in Inuit Art Quarterly 1998:40).

Uqaituk chooses to work only with hand tools since he loses the connection with the stone when he uses power tools. When he begins a carving, he starts by sawing off excess stone, then chipping away at it with an axe until the shape resembles the idea he has in his mind. “Sometimes, when you look at a piece of stone, it already has a shape” (ibid.). When the carving is nearly finished, he makes the surface smooth with sandpaper and meticulously adds details.

Uqaituk’s sculptures consist largely of narrative scenes, however “he will sometimes draw from the supernatural world of the Inuit and present beings that are half-human, half-animal. At other times, he highlights the grace of animals in his environment” (FCNQ 2009).

“Uqaituk’s style combines all the characteristics of sculpture from Inukjuak: a sense of movement, the catching of an activity at a specific moment, and the play on the contrast between the light and dark, smoothly polished surface areas” (ibid.).

In 2001, Bombardier presented one of Uqaituk’s carvings, entitled Father and Son Fishing, to U.S. President George W. Bush.

“Uqaituk’s early works were done in a style that many Inukjuak artists had adopted at that time. They preferred to work the stone on the surface, rarely cutting through the stone in their work because the stone was hard and because artists used very basic tools. By the early 1990s, Jobie had refined his work and his sculpture became sought after by collectors. His pieces had become more dramatic, with strong lines and thoughtful composition” (FCNQ 2009).

2009 “Jobie Uqaituk : Biographies/Career,” Art Nunavik. Art Nunavik PDF (accessed 25 February).

1998 “Jobie Ohaituq: ‘Carving is not just for recreation,’” Inuit Art Quarterly (IAQ), vol. 13, no. 3 (Fall): 40.