He had the courage to be what he wanted to be and succeeded in creating and sustaining his own image. He was sufficient unto himself and did not depend upon outside approbation.”

(Myers [Mitchell] in Joe Talirunili: “A grace beyond the reach of art”)

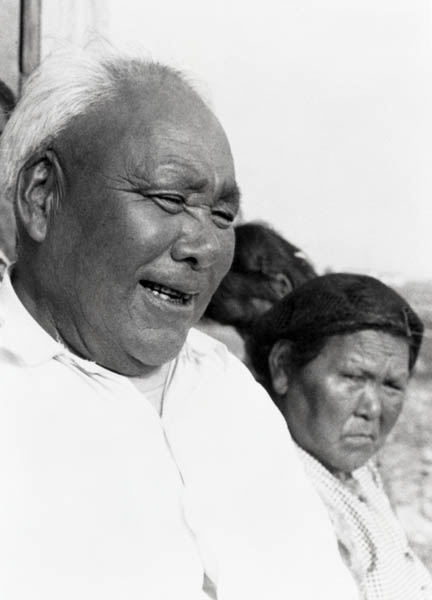

Born in 1906 in Kuujjuarapik (Great Whale River).

Talirunili’s Migration sculptures and prints were based on a significant event in his life that involved a crossing from an island in Hudson’s Bay to the mainland. Nearly trapped by crushing ice, he recalled that his grandmother prayed to God, and a safe passage was provided through the ice: “We landed in a place that was very steep. We had to take a rope and when we got to the shore, we secured the boat to the shore with this rope. During that time, for almost a week, the wind blew very hard and we could not move from where we were. That was the time my mother said that we might be having to eat each other because we were so hungry. The weather changed at last and when the ice slackened off, we went to find some people” (Talirunili in Myers [Mitchell] 1977:30).

Sculpture and drawing.

“Talirunili’s instincts stood him in good stead, in his life as in his art. If a piece broke off while he was working the stone, Joe, undaunted, stuck it back with putty or glue or whatever else happened to be at hand, making no effort to be subtle about it either. He appeared never to have spent much time searching for just the right piece of stone, but would settle for just any old piece of rock he happened to find lying around. Often as not, he made it more interesting by colouring it with crayon, usually green, or ball point pen” (Myers [Mitchell] 1977:4).

Animals (especially owls), boats, and human figures. Art historian Celine Saucier wrote that Talirunili took a “very personal approach” toward his human figures: “The hair is tidy and the faces are good-natured. The women he carved always wear an amauti, and often stand sturdily with their legs slightly apart and their feet firmly fixed to the ground” (Saucier 1998:114). Curator Maria von Finckenstein says: “Talirunili had a limited repertoire of themes for his sculptures. Besides the boat scenes, he restricted himself to frontal animal and human figures,” which, she notes, are “typically devoid of movement and heroic gestures” (von Finckenstein 1998:9).

Talirunili’s sculptures often include plastic, string, and wood, appear fragile without bases, and are unpolished” (Lucassie Tookalook in Mitchell 1998:16).

Migration, a sculptural representation of the aforementioned boating journey gone awry, was depicted on a 14-cent Canadian stamp in 1976. In 2006, one of his Migration sculptures sold at Waddington’s Auction for $278,000 — the highest price ever achieved for a single Inuit artwork.

1998 “Making Art in Nunavik: A Brief Historical Overview,” Inuit Art Quarterly (IAQ), vol. 13, no. 3 (Fall): 9.

1998 “Making Art in Nunavik: A Brief Historical Overview,” Inuit Art Quarterly (IAQ), vol. 13, no. 3 (Fall): 4–17.

1977 Joe Talirunili: “A grace beyond the reach of art.” Toronto: Herzig Somerville Limited.

1998 Guardians of Memory: Sculpture Women of Nunavik. Quebec: L’instant même.