. . . I am always carving, the only time it gets hard is if there is no stone to carve.”

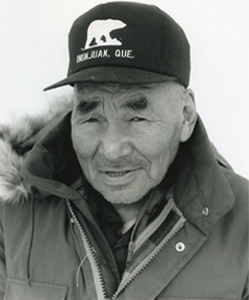

(Johnny Inukpuk in an unpublished interview with the Inuit Art Foundation, 1998)

Born in 1911, in Kujjuarapik.

Inukpuk began carving while living on the land. After moving to Inukjuak in the 1950s, James Houston encouraged him to continue carving. “The carvings back then used to be really cheap. Saumik [James Houston] was the one who encouraged people to carve, so I did. Carving gave us independence. . .” (Inukpuk in Inuit Art Quarterly 1998:30).

Sculpture and one print. In 1974, he made a single print, entitled A True Story of Johnny Being Attacked by Three Polar Bears While in His Igloo, to document a real life hunting experience of his. To quote Marybelle Myers [Mitchell]: “While hunting one winter, Johnny built himself a small overnight igloo. He was caught unaware by three polar bears, and, since he had left his rifle outside, had to fend them off with a stick. Though he was a famous carver, he felt that he could not adequately tell this story in stone. He discussed it with the hunters in his community and, together, they decided the tale could best be told by means of a stonecut print. Johnny knew nothing about printmaking, but his inspiration guided him to the creation of a sincere and charming print” (Myers [Mitchell] 1974:2).

Childrearing, domestic and hunting activities

Inukpuk’s wife, Mary, had a hare-lip, which was depicted in several of his female sculptures. The drilled eyes of his earlier works were eventually replaced by soapstone and ivory inlay; black eyes were made from melted vinyl records. In 1953, Inukpuk began carving green stone that was described by curator Darlene Wight as being “characterized by pronounced translucent layers that glow in the light and by gold patches that enhance this opalescent effect” (Wight 2006:84). His characteristically shiny, round heads began to appear in 1954.

In 1973, Inukpuk was elected a member of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts.

Art historian Ingo Hessel says that, after early experimentation, Inukpuk had developed his own style by 1955. His work evolved from small-scale pieces to larger, more-personal artistic statements (Hessel 1998:64, 80).

With the TD Bank Financial Group’s 1951 purchase of Hunter, possibly the first large figure produced by a Canadian Inuk at that time. Inukpuk’s work was also included in Eskimo Carvings, an exhibition organized by Gimpel Fils gallery in London, England in 1953.

1998 Inuit Art: An Introduction. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre.

1999 “‘We wouldn’t be doing what we’re doing if it weren’t for him’: Inuit recall being encouraged to carve by James Houston,” Inuit Art Quarterly (IAQ), vol. 14, no. 3 (Fall): 24–30.

1977 “In the Wake of the Giant,” Port Harrison/Inoucdjouac. Winnipeg: Winnipeg Art Gallery.

1974 “Arctic Quebec 1974 II,” Arctic Quebec II (catalogue). Montreal: La Fédération des Coopératives du Nouveau-Québec: 2–3.

1990 “Regional Diversity in Contemporary Inuit Sculpture,” Inuit Art Quarterly (IAQ), vol. 5, no. 3 (Summer): 10–23.

1998 Guardians of Memory: Sculpture Women of Nunavik. Quebec: L’instant même.

1992 Sculpture of the Inuit. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart.

2006 Early Masters: Inuit Sculpture 1949–1955. Winnipeg: Winnipeg Art Gallery.