I try to encourage younger people to carve. I emphasize the fact that young people should follow the traditions of their forefathers. It seems to me that our culture will die off one day if we do not keep carving. . . . In spite of the hard work required to quarry stone in the winter, when the rock is covered with snow, I do it in the hope that our culture will be passed on through our carvings. If the carvers were to all die, we would not have anyone to carry on the tradition that we have continued through our carvings.”

(Johnny Aculiak in Inuit Art Quarterly, 1997)

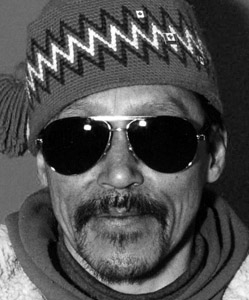

Born in 1951, on one of the Hopewell Islands north of Inukjuak.

Aculiak said he could not remember the exact date he devoted himself to carving, although he probably began as a way to support his family after his father died in 1968. In the beginning, Aculiak said he envied the carving skills of his friends: “They could do what I couldn’t. That gave me a lot of anxiety, not being able to carve like them. I really wanted to learn. When I was young, I would work away on a carving until someone came along. Then I would quickly pretend I was not carving. I used to be ashamed, thinking that my carvings were not good enough for people to look at. All the time I was carving, I would keep an eye out to see if people were coming my way. Eventually, I lost my shyness about carving” (Aculiak in Kudluk 1997:24).

Aculiak was best known for his stone sculpture; he also made drawings and jewellery.

Aculiak preferred to work with hand tools rather than power tools, and he felt that there should be a distinction. “I think that carvings made with hand tools should be separated from the carvings made with power tools. I think that carvings made by power tools are overpriced” (Aculiak in Kudluk 1997:26). He acknowledged, however, the limitations of hand tools: “It is a challenge for me to make what I want without the use of power tools” (ibid.). Occasionally, Aculiak added ivory or caribou antler to his soapstone carvings. He also quarried his own stone, a task he said was challenging. “It is not an easy job to quarry stone. Every year we have to find a boat to take us to the stone. The boat often has a leak and doesn’t have a proper pump to drain water, which means that we have to drain water from the boat by hand. And when we get to the quarry site, we have to take the rock out of the ground without proper quarrying tools” (ibid 27). Aculiak’s wife, Lily, helped polish his sculptures after he cut a muscle in one of his fingers.

Aculiak’s sculpture depicts the Inuit way of life. He also accepted commissions for specific subjects. “I would get requests from teachers who wanted me to make something specific for them. I would always try, even if I had never made it before. Mostly they wanted birds. I was already being told that I was a good carver, even when I had no idea of how to price a carving” (Aculiak in Kudluk 1997:24).

Aculiak’s sculpture is highly polished and contains such fine details as facial expressions and hunting tools.

In 1987, Aculiak and his wife travelled to Europe and Russia, accompanying Things Made by the Inuit, an exhibition organized by La Fédération des Coopératives du Nouveau-Québec.

1997 “Johnny Aculiak: ‘It seems to me that our culture will die off one day if we do not keep carving,’” Inuit Art Quarterly (IAQ), vol. 12, no. 4 (Winter): 24–28.